Xenolinguistics: the scientific study of languages of non-human intelligences. Publications in this field tend to be speculative as few people have made the claim to have understood an alien language, at least not reliably.

—Wikuniversity

Hallucinations as Alien Art

The key to this discussion is a conceit of the extraordinary vision-producing ability unleashed in consciousness by psychedelics, as alien art: aesthetic productions of an unknown, hence alien, source. Whether the alien is an unknown (normally unconscious) aspect of the Self, an Other, or a blended configuration of Self and Other, can be held in abeyance as part of the high strangeness of the experience. Alien art is construed as an epistemological strategy of the Other in the psychedelic sphere for knowledge acquisition and transmission. This view is in sharp contrast to the notion of hallucinations as mechanically generated “form constants,” abstract geometries with no semantic dimension per se. (1) It is closer to the narrative and highly significant (for the experiencing individual) 1st person reports in Shanon’s ayahuasca phenomenology. (2) These aspects of alien art describe features of the visual field that can simultaneously involve cognitive processes accompanied by vivid feeling states; bodily sensations (or lack thereof); and the synaesthetic involvement of other senses. Alien art begins with conditions of extended perception, an ascending scale of effects from the sensory amplifications of cannabis and hashish through the full-scale wraparound realities of high-dose sessions of DMT, psilocybin mushrooms, and LSD. These visionary states and content are frequently experienced as going beyond the pleasures of “great visuals” or “psychedelic eye-candy” to their rhetorical and noetic function, with aesthetics and visual languages employed to deliver a teaching, an insight, a revelation or prophecy, or the sought answer to a problem. It is this signifying and hence, in the most basic sense, linguistic aspect of the psychedelic experience that I am calling Xenolinguistics.

The Alien Dimension in Psychedelic Experience

The mythologem of the alien encounter—UFOs; abduction scenarios; prophetic channelings; generations of Star Trek; and cult religions such as Heaven’s Gate and the Raelian dispensation—have haunted the cultural fringe since the mid-20th century brought the first sightings of lights in the sky. These realtime ingressions of alien novelty were preceded by decades of science fiction speculations. Xenolinguistics—the search for, creation and study of alien languages—has strong connections to science fiction and fantasy, and to the activity of constructing languages, represented by a small but highly communicative sub-culture of “con-langers.” Xenolinguistics connects to the scientifically framed S.E.T.I. discourse on interstellar messaging, (3) and appears as a theme in the literature of psychedelic self-exploration, particularly in the work of Terence and Dennis McKenna. (4) John Lilly’s work in interspecies communication with dolphins led to his inclusion in the first S.E.T.I. meeting about interstellar messaging and the search for intelligent life in the cosmos. Lilly went further with his researches by combining his technology of sensory isolation tanks with the technology of psychedelic psychopharmacology. Both his methods and his findings placed him outside the pale of institutionally approved science, especially as he reported extensive communication with extraterrestrial intelligence via the Earth Coincidence Control Center (E.C.C.O.) and described new forms of linguistic activity in the psychedelic sphere. (5) The other major outlaw scientist of the psychedelic sphere, Timothy Leary, received his own extraterrestrial download, The Starseed Transmission, while in solitary confinement in Folsom Prison.

The psychedelic sphere is reported by practicing shamans, mainstream and outlaw scientists, and psychedelic self-explorers to be populated by communicating entities. Horace Beach’s 1996 dissertation, “Listening for the Logos: A Study of Reports of Audible Voices at High Doses of Psilocybin,” (6) finds that of a sample of 128 participants (with experience with psilocybin), better than a third experienced communications with a perceived voice. The DMT (dimethyltriptamine) archives at the Vaults of Erowid, (7) a database of psychedelic information, have many reports of encounters with entities while in the tryptamine trance, some of which include reports of alien language. (8) The literature of shamanism contains pantheons of helpful and malign spirits, guides, allies, gods and demons, angels, extraterrestrials, and ancestors. (9, 10) Within these persistent experiences of encounters with entities can be found reports of new forms of language deployed in these contacts with the Other, and a complex of related notions about language, consciousness, and reality. There is an aspect of each of these perspectives on alien language in my own work: a fictional, constructed language within a story world; the S.E.T.I. discourse; and contact and communication with the Other in psychedelic self-exploration. I will focus on the role of psychedelic self-exploration which resulted in the creation and explication of an alien language, Glide, through a novel The Maze Game, (11) academic research, (12) and the development of interactive software as writing instruments for this visual language. (13, 14)

Psychedelic Science

Psychedelic Science incorporates many disciplines in its search for understanding of human experience with these mind-altering substances, a history that appears to go back to the earliest signs of culture in cave paintings and remains in Europe and Africa. (15) Neuroscience, physiology, microbiology, biochemistry, paleo-anthropology, ethnobotany, philosophy, rhetoric, and consciousness studies all play a role. It may seem obvious that first person reports are necessary to communicate the experiences and provide matching data to whatever third person observations (physiological signs, neurological imaging of brain activity, chemical structure-activity analyses) are made. However, the treatment of subjectivity within consciousness studies is contested ground. (16)

Consciousness itself had been operationally disbarred from scientific discourse in the early 20th century as psychology turned to behaviorist models (17) and empirical methods, excluding all forms of subjective introspectionism. Psychophysics, with its experimental designs, accepted subjective reports about clearly defined bits of perception, memory, and cognition as reliable enough to produce repeatable experiments, verifiable and useful generalities and even laws. Characterizing the nature of the Self, the I that deems itself conscious and reflects on the content and operations of consciousness, is dependent on one’s epistemological biases. The concept of Self is inextricably connected to the concept of the Other; the dichotomy of subjective and objective; observer and observed; and, following James, the knower and the known. In consciousness studies, Self and Other are assumed as stable, if not universal, categories; (18) the discussion and use of first and third person methods in the study of consciousness assumes this structural stability. Within consciousness studies, the material reductionist position, held by Dennett, Churchland, and Hardcastle, treats mind (including Self-concept) as an epiphenomenon of matter. (19) Mind and subjectivity are defined, if not out of existence, certainly to a non-fundamental status. These issues become even more problematic in psychedelic mindbody states, as the experience of the differentiation between Self and Other is radically re-organized in ways ranging from a mystical merging into Oneness through a plethora of encounters and relations: teaching and guidance; erotic interchange; adversarial struggles; many forms of paradoxical both-and relations, and group mind experiences which have no parallel in ordinary reality.

Reality is a critical concept in psychedelic science. The ontological status of experiences in the psychedelic sphere is inevitably called into question, both from within firsthand experience, and when these reported experiences are interpreted by others who may or may not have had similar experiences. A high degree of novelty, and the bizarre (from a baseline perspective) qualities of what can be seen, heard, and felt, sometimes deeply and profoundly, can be experienced in altered states. It is this “high strangeness” that provides the opening for labeling the experiences themselves “unreal,” and therefore unworthy of serious study, or merely symptoms of mental disorder. I have written on this topic elsewhere, characterizing psychedelic science as “the discourse of the unmentionable by the disreputable about the unspeakable.” (20)

Reality and perception are tightly coupled, as Roland Fischer’s model of the perception—hallucination continuum depicts. (21)

In simplest terms, when perception changes, what we construe to be reality changes. Charles Tart built models of levels or states of consciousness, and called for the introduction of state-specific sciences, and the possibility of state-specific language to adequately deal with the different realities perceived in altered states. (22)

John Lilly’s protocols reflect the problem from a methodological standpoint:

In a scientific exploration of any of the inner realities, I follow the following metaprogrammatic steps:

1. Examine whatever one can of where the new spaces are, what the basic beliefs are to go there.

2. Take on the basic beliefs of that new area as if true.

3. Go into the area fully aware, in high energy, storing everything, no matter how neutral, how ecstatic, or how painful the experiences become.

4. Come back here, to our best of consensus realities, temporarily shedding those basic beliefs of the new area and taking on those of the investigator impartially dispassionately objectively examining the recorded experiences and data.

5. Test one’s current models of this consensus reality.

6. Construct a model that includes this reality and this new one in a more inclusive succinct way. No matter how painful such revisions of the models are be sure they include both realities.

7. Do not worship, revere, or be afraid of any person, group, space, or reality. An investigator, an explorer, has no room for such baggage. (23)

When one is engaging communication with the Other in the psychedelic sphere, it pays to have protocols. Lilly’s protocol privileges neither the ordinary nor the non-ordinary states of consciousness, but attempts to include both in the construction of a new model of reality of multiple mind-states and multiple realities. Terence McKenna and Lilly both recommend never giving up one’s skeptical stance. McKenna is also clear on the necessity of reporting the subjective content. When describing the structure-activity of a psychedelic substance, the language of biochemistry reveals none of the high strangeness of the experiences. Describing the content of a visionary state—the images, environments, novel space-time configurations, denizens, languages, and information acquired in the experience—is often much less palatable to the scientific world-view.

My approach is simply this: to take the phenomenological position of saying what was personally seen and experienced as accurately as possible, not editing out information just because it strains credulity, or demands continual repair to my worldview, or that of my readers. Part of the phenomenological epoche or bracketing in this effort consists in setting aside the drive to determine the ontological status of the experiences, especially since abstractions such as “reality” can themselves be radically re-configured in the psychedelic sphere. Further, I examine the reports of others, however unsettling, with the same good faith, engaging in a comparison of texts, essentially a literary and rhetorical activity, with no claims made as to the “reality”, in baseline terms, of the findings. The correlations among texts provide sufficient intrasubjective validation to indicate the possibility that the authors of the reports have spent time in realities sufficiently similar to establish, not a consensus—there are far too few in-depth reports gathered over multiple sessions—but perhaps a set of recognizable landmarks that can form the first sketches of maps of a “reality” that includes these experiences. This may seem an epistemologically primitive method, when compared to the scientific paradigm, yielding no proofs, no reliably repeatable experiments, and few samples to examine. Yet, as David Turnbull argues, “scientific knowledge can be seen as “the contingent assemblage of local knowledge.” I suggest it is a starting place toward subjective (personal, first person, individual) psychedelic knowledge, building a collection of what David Turnbull terms “local knowledges.” These localities can be as particular as a single individual’s three-paragraph trip report posted to Erowid; as extensive as a single individual’s lifework; or as comprehensive as the collective practices and knowledge of a culture, such as the Mazatec mushroom culture, the Peyote Way, or an ayahuasca culture, such as Santo Daime, União de Vegetal, or Barquinha. Each locality, from the individual to the group produces its own accounts of experience in the psychedelic sphere, its own descriptions of the landscapes, its own sense of the intentionality of the voyage from baseline outwards/inwards and return to ordinary reality. From these experiences descriptions are written, interpretations arise, songs, paintings, software, and dances emanate; rituals are enacted. A body of knowledge collects. Maps can be envisioned, landmark by negotiated landmark.

Xenolinguistics

Xenolinguistics, in my usage, is the study of language and linguistic phenomena in the psychedelic sphere. Xenolinguistics gives a word to this effort to create a first assemblage of local knowledges, gathered from first person reports, as from the logbooks of early navigators, about these phenomena. The local knowledges I am interested in are those of the xenolinguists, where the focus, fascination, and subsequent interpretations circle around language—different capacities of language from what we call “natural” language. Xenolinguistics reveals forms of language and theories about language itself, and its functioning in the brain/mind, in culture, and in evolutionary processes, both genetic and cultural.

Krippner reports in 1970 on a variety of distortions of natural language use under the influence of psychedelics, with instances given of both increased and decreased functioning. (24) Roland Fisher studied the effects of psilocybin on handwriting; his experiments had the participants copying passages of writing while under the influence; the writing becomes larger, rounder, more fluid. (25) Henry Munn in his writings on curandera Maria Sabina speaks of heightened eloquence, and of the evolution of writing under the influence of psilocybin.

“Language is an ecstatic activity of signification. Intoxicated by the mushrooms, the fluency, the ease, the aptness of expression one becomes capable of are such that one is astounded by the words that issue forth from the contact of the intention of articulation with the matter of experience. At times it is as if one were being told what to say, for the words leap to mind, one after another, of themselves without having to be searched for: a phenomenon similar to the automatic dictation of the surrealists except that here the flow of consciousness, rather than being disconnected, tends to be coherent: a rational enunciation of meanings. Message fields of communication with the world, others, and one’s self are disclosed by the mushrooms. The spontaneity they liberate is not only perceptual, but linguistic, the spontaneity of speech, of fervent, lucid discourse, of the logos in activity. For the shaman, it is as if existence were uttering itself through him.” (26)

This vision of language as a universal ecstatic form of signification, of its source in the Other (“automatic” writing; the mythologies of language origin), and of eloquence that expresses itself visually in a bootstrapping move into new forms of language is a particular feature of the psilocybin trance. Munn describes this process as it is experienced in Mexican cultures:

“The ancient Mexicans were the only Indians of all the Americas to invent a highly developed system of writing: a pictographic one. Theirs were the only Amerindian civilizations in which books played an important role. One of the reasons may be because they were a people who used psilocybin, a medicine for the mind given them by their earth with the unique power of activating the configurative activity of human signification. On the mushrooms, one sees walls covered with a fine tracery of lines projected before the eyes. It is as if the night were imprinted with signs like glyphs. In these conditions, if one takes up a brush, dips it into paint, and begins to draw, it is as if the hand were animated by an extraordinary ideoplastic ability. Instead of saying that God speaks through the wise man, the ancient Mexicans said that life paints through him, in other words writes, since for them to write was to paint: the imagination in an act constitutive of images. “In you he lives/ in you he is painting/ invents/ the Giver of Life/ Chichimeca Prince, Nezahualcoyotl.” Where we would expect them to refer to the voice, they say write. “On the mat of flowers/ you paint your song, your word/ Prince Nezahualcoyotl/ In painting is your heart/ with flowers of all colors/ you paint your song, your word/ Prince Nezahualcoyotl.” (27)

Maria Sabina, curandera.

One of the major themes of Terence McKenna’s lifework is the explication of the linguistic phenomena released in the tryptamine trance, and his speculations on the relationship of this phenomena to the cultural evolution of the human species. For McKenna, language is fundamental to reality and its construction.

“Reality is truly made up of language and of linguistic structures that you carry, unbeknownst to yourself, in your mind, and which, under the influence of psilocybin, begin to dissolve and allow you to perceive beyond the speakable. The contours of the unspeakable begin to emerge into your perception and though you can’t say much about the unspeakable, it has the power to color everything you do. You live with it; it is the invoking of the Other. The Other can become the Self, and many forms of estrangement can be healed. This is why the term alien has these many connotations.” (28)

The specific connection of new language and psilocybin is made:

“What does extraterrestrial communication have to do with this family of hallucinogenic compounds I wish to discuss? Simply this: that the unique presentational phenomenology of this family of compounds has been overlooked. Psilocybin, though rare, is the best known of these neglected substances. Psilocybin, in the minds of the uninformed public and in the eyes of the law, is lumped together with LSD and mescaline, when in fact each of these compounds is a phenomenologically defined universe unto itself. Psilocybin and DMT invoke the Logos, although DMT is more intense and more brief in its action. This means that they work directly on the language centers, so that an important aspect of the experience is the interior dialogue. As soon as one discovers this about psilocybin and about tryptamines, one must decide whether or not to enter into the dialogue and to try and make sense of the incoming signal.” (29)

Observing the varied effects of tryptamines on language, McKenna developed a theory that it was the encounter of early humans with the mushroom that potentiated the development of language. Plant knowledge would be one of our earliest forms of expertise as hunter-gatherers, discovering not only foods from every part of plants (roots, stems, leaves, berries, nuts) but also their medicinal and mind-altering properties. The merit of this speculation is more easily accessed from within the experience itself. From this perspective, the development of computer graphics and animation raise the possibility that new forms of language, particularly visual language, are emerging in our culture.

A Few Aspects of Alien Art

The perceptual events which I am calling alien art forms occur, by definition, under conditions of extended perception, a sliding scale of alterations from the commonly observed enhancement of music heard or produced under cannabis intoxication (30) to the high-speed, multidimensional visual linguistic constructions morphing at warp-speed in the DMT flash, and the unfolding of epic historic tableau under ayahuasca. (32) They are characterized by a sense of high information content in a high-speed “download.” Simon Powell describes this high information content as a function of moving to “higher” forms of language, especially symbolic language.

“The symbol embodies a whole set of relations or, to be more specific, it is the point where a huge web of psychological relations converge. To fully understand the symbol is to sense at once all of its relations to other objects of perceptual experience. In other words, visual symbols play a role in a psychological language. (Here, I again invoke the concept of language since language is essentially an information system not restricted to words alone. Language, in the abstract way in which I refer to it, is a system of informational elements bearing definite relations with one another; hence a language of words, of molecules, of symbols, etc.)

Such universally powerful visionary symbols can be thought of as expressions in the dictionary of a ‘higher’ language connected with the human psyche. What I mean by ‘higher’ is that the visual elements in this language are far more rich in meaning and informational content than the words of our spoken language. Moreover, the direct perception of visionary symbols choreographed together in a movie-like fashion—as occurs in the entheogenic state—is to experience meaning in perhaps its purest, most informationally rich way. To partake of a visionary dialogue is to be overwhelmed by the direct apprehension of naked, unmuddled meaning, which arises as a consequence of the highly integrative informational processes liberated by shamanic compounds.” (33)

The “unspeakability” or “ineffability” of psychedelic experience appears to be not only an expression of the inadequacy of natural language to express certain experiences, but basic to the nature of the specific linguistic vehicle. Natural language is simply too slow a software to carry the complexity, the simultaneity of multiple meanings, and the speed and quantity of cognitive connections among ideas and images flooding into a psychedelic mindbody state. These perceptions of increased velocity–of thought and of sensory data–seem related to the experience of time dilation in the psychedelic sphere. Time dilation is a function of cognitive and sensory speed and the quantity of information per unit of time: hyperconnectivity, hyperconductivity, and processor speed. When novelty approaches infinity, realities fly apart. Hence: xenolinguistics.

Powell continues:

“Such types of symbol can therefore be considered elements of a high language, a language not of the individual ego-driven mind but of the communicating Other. The symbols are amalgamated concentrations of information coming to life in a mind illuminated by visionary alkaloids. Or, to us Huxley’s terminology, the informational forms are transmitted via the psilocybinetic brain. In either case, a Great Spirit, a sacred presence, or Gaian Other reveals itself as being no less than a tremendously vast system of confluential information flowing through the psychedelically enhanced neuronal hardware of the human cortex. As information ‘struggles’ to integrate, ever more coalescent forms emerge, and these are experienced as the felt presence of the Other actively communicating in a language of potent visual imagery. Information appears as if alive and intent upon self-organization.” (34)

This passage points to the experience where psychedelically potentiated language and communicating Other appear to merge into a living language. McKenna’s many descriptions of “self-transforming machine-elves” and my own perception in altered states of Glide as a living language that teaches about itself as well as many other things seem to belong to similar narratives of experience. This perception of living language in motion and constant transformation takes the self-reflexive activity of using language to describe itself to a meta-level of function, where the language gains the self-reflective quality of consciousness, in communicating about itself—and just about anything else in the universe one may be wondering about.

This alien art of hallucinatory presentation of information is often accompanied by a set of qualities that extend baseline perception. These qualities can include deeper, richer, more varied, more subtle, and in some cases new colors that make up the visual palette. The complexity and density of the informational field is in part accompanied by an increased amount of very fine cognitive detail and a concomitant shift in the amount of detail from the sensory systems. Attention, a primary function of consciousness, presents a panoply of aesthetic choices, shifting its qualities, in some cases toward an increased slipperiness (a hyper-conductivity), sliding frictionlessly from one point of focus to another. At other times, attention becomes the ability to focus in stillness, to hold an awareness not only of the object(s) of contemplation but of the awareness itself, a kind of ‘witness consciousness’ or mindfulness that allows direct perception of the goings-on in one’s mind. One becomes aware that attention can partake of qualities like touch—rough, focused, gentle, smooth, and/or erotic and applied with various admixtures of emotion.

Layering, Transparency, Iridescence

Another visual/cognitive quality that emerges is the layering of visual imagery. This can appear accompanied by subtle and shifting degrees of transparency and iridescence, of soft flows combined with extremely precise fine filamental structures and a sense of having X-ray vision and microscopic vision as controllable aspects of the visual field. Macroscopic visions of the structure of the cosmos at astronomical scales can also be presented to consciousness. Transparency becomes a metaphor for all manner of seeing-through, revealing in the combined sense of seductive veils and of revelation of a truth, a hide-and seek God game of gnosis—now you see Me now you don’t—of quest and question, a noetic dance in realms wholly outside our natural language’s labels and cognitive ordering schemes.

The high-information content aspect of alien art is not a matter merely of quantity of information but can be imbued with qualities such as fecundity, a sense of an abundance of creativity in the flood of images and ideas, and often a prevailing mood, of playfulness, or numinosity, or strange juxtapositions of mood, such as sacred silliness or a combined cathedral and carnivalesque architecture, each mood generating a seemingly endless fount of aesthetic styles.

Patchworking

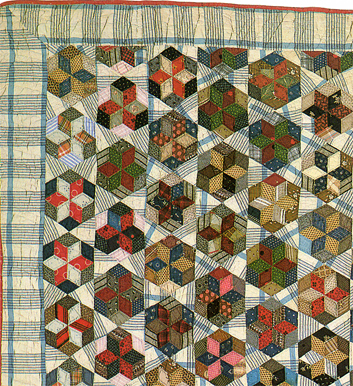

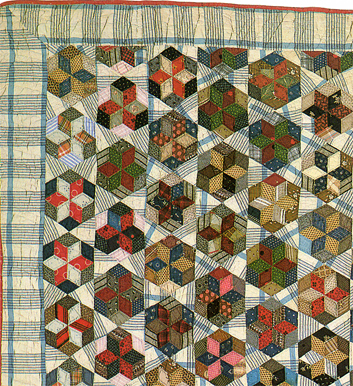

Patchworking describes a complex collage-like cognitive-visual process by which different, sometimes drastically diverse, bits of vision-knowledge begin to collect and arrange themselves into larger patterns that incorporate, recombine, and transform the meanings of the individual pieces. Quilt-making is such a process. The illustrated quilt brings together hundreds of diamond and triangular patches from discarded clothing, carefully re-cycled into a design that incorporates two and three-dimensional visual aspects. The design shifts depending on whether you view the material within the hexagons as flat six-pointed stars, or as baby blocks (Necker cubes). In the baby-blocks view, one can see two different perspectives. Each perspective in turn recombines the order of the available patches. The surface, playing with these illusions, shifts and moves dynamically among dimensions, as the different views pop in and out of the visual field. A kaleidoscope, containing a handful of irregular bits and pieces of colored glass and other materials, constructs a complex, shifting, symmetrical, non-repeating stained glass window of colored light. In my own session reports I describe patchworking as making “harmonious compositions out of impossibly disparate items without breaking the narrative dream but rather expanding its inclusiveness.” (36) Patchworking in altered states assists in “layering realities,” and is “a practice to acclimate you to staying in multiple spaces that are incongruous, non-contiguous, seemingly dissonant.” McKenna describes this patchworking aspect in True Hallucinations, which is the detailed account of the “experiment at La Chorrera,” and the mutual inhabitation by Dennis and Terence McKenna of an interpenetrating altered state of consciousness that lasted several weeks brought on by the ingestion of psilocybin mushrooms.

“Occasionally I would seem to catch the mechanics of what was happening to us in action. Lines from half-forgotten movies and snippets of old science fiction, once consumed like popcorn, reappeared in collages of half-understood associations. Punch lines from old jokes and vaguely remembered dreams spiraled in a slow galaxy of interleaved memories and anticipations. From such experiences I concluded that whatever was happening, part of it involved all the information that we had ever accumulated, down to the most trivial details. The overwhelming impression was that something possibly from outer space or from another dimension was contacting us. It was doing so through the peculiar means of using every thought in our heads to lead us into telepathically induced scenarios of extravagant imagining, or deep theoretical understandings, or in-depth scanning of strange times, places, and worlds. The source of this unearthly contact was the Stropharia cubensis and our experiment.” [emphasis mine] (37)

Patchworking appears to be an aesthetic strategy whereby the Other, using the stored personal information, emotions, and memories of the individual, constructs new forms and configurations of knowledge about our existing reality, its past and future, and about other worlds and other realities with profoundly alien—different from baseline reality—content. This alien content: vast machineries, strange energies, different time-space schemata, whole worlds operating on different physical principles, or our own world viewed from a profoundly different consciousness, reveals other rules of organization of worlds, such as underlying structures of reality based on games. Patchworking ecstatically rejoins that which has been dismembered, fragmented, or never connected in the first place in meaningful patterns. As such it shares a functional pattern with the shamanic initiatory experience of dismemberment and rebirth in a new recombinatory body which can travel between worlds and hold consciousness of multiple worlds at once.

Glide and LiveGlide

My own work, the core of which was developed before the encounter with the McKennas’ work, has the shape of an adjacent mythology: a narrative of language origin in psychedelic experience. Glide is an experiment in modeling a visual language whose signs move and morph. It originated in a work of speculative fiction, The Maze Game, (Deep Listening Press, 2003) as an evolutionary form of writing from 4000 years in the future. Its myth of origin speaks of a transmission of the language to the Glides from the hallucinogenic pollen of giant blue water lilies which they tended. I followed the traditional Glide path for learning the language: study and practice both at baseline mind-body states and cognitively and sensorially enhanced psychedelic states. Part of the learning involved building electronic writing instruments. (38) The colors and patterns applied to the transforming glyphs come from drawings, photos, and video by myself and others. LiveGlide is most at home in live performance in a domed environment, such as planetarium, but can be shown as recordings on a flat-screen format as well.

Interacting with this visual language—designing the software, then reading and writing with it, especially in altered states, as a noetic practice, has led to a constellation of ideas about the relationship between language, consciousness, and our perception and conception of reality. One cluster of ideas begins with the notion of the hallucination as alien art. It is in part a rhetorical notion, that aesthetics is part of the impact of these novel states of consciousness and their contents. The communication with the Other, the entire noetic enterprise, is baited with beauty as part of its persuasive force. This led to the observation and delineation of techniques deployed by the Other in the communicative process in altered states, often hallucinatory.

As to the shifting faces and perceived identity of the Other, many notions have been forwarded. SF writer Philip K. Dick called the Other V.A.L.I.S.—Vast Active Living Intelligent System. John Lilly called it E.C.C.O.—Earth Coincidence Control Center. Terence McKenna called them self-transforming machine elves, and has also experienced the alien Other as insect-like. I call them the Glides, and they are shape-shifters as well. But within these experiences, these definitions shift as explanations are sought. Are these others actually another aspect of the Self, buried in the unconscious? This may be more comforting than scenarios of actual alien contact, and is an assumption upon which arguments for mental disorder can be built, but has little explanatory power, other than to reveal the grab-bag nature of the way the term “unconscious” is used to contain any number of mysteries of human nature. An open mind and a sense of humor may be the best provisional approach to such questions. As the Sundance Kid repeats the plaintive question, “Who are those guys anyway?” and Walt Kelly offers through Pogo, “We have met the enemy and he is us,” we can contain the cosmic giggle bubbling up through such speculations at baseline. Yet in the experience itself, it can seem as Simon Powell puts it:

“Such chemically inspired neuronal patterning is experienced as being so rich in symbology and meaning that for all intents and purposes it can be considered the result of a living, intelligent, and communicating agency made of information, an agency whose intent can become focused should the chemical conditions of the human cortex be so conducive. Information must indeed be in some sense alive.” (39)

(1) Kluver, Heinrich. Mescal and Mechanisms of Hallucinations. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1969.

(2) Shanon, Benny. The Antipodes of the Mind: Charting the Phenomenology of the Ayahuasca Experience. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2002.

(3) S.E.T.I.

(4) McKenna, Terence and Dennis McKenna. The Invisible Landscape: Mind, Hallucinogens, and the I Ching. San Francisco: HarperCollinsSanFrancisco, 1993.

(5) Lilly, John. The Center of the Cyclone: An Autobiography of Inner Space. New York: Bantam Books, 1979.

(6) Beach, Horace. “Listening for the Logos: A Study of Reports of Audible Voices at High Doses of Psilocybin.” Ph.D. dissertation, California School of Professional Psychology, Alameda, California, 1996.

(7) Erowid

(8) http://www.erowid.org/experiences/exp.php?ID=1859

(9) Shanon, 2002.

(10) Polari de Alverga, Alex. Forest of Visions: Ayahuasca, Amazonian Spirituality, and the Santo Daime Tradition. Rochester, Vermont: Park Street Press, 1999.

(11) Slattery, Diana Reed. The Maze Game. Kingston: Deep Listening Publications, 2003.

(12) https://mazerunner.wordpress.com

(13) http://www.academy.rpi.edu/glide

(14) http://web.mac.com/dianaslattery/iWeb/Eye/work-I.html

(15) Nichols, David E. “Hallucinogens,” Pharmacology & Therapeutics 101 (2004) 131—181.

(16) Wallace, Alan B. The Taboo of Subjectivity: Toward a New Science of Consciousness. New York: Oxford University Press, 2000.

(17) Baars, Bernard J. In the Theater of Consciousness: The Workspace of the Mind. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1997.

(18) Baars, 1997.

(19) Shear, Jonathan, ed. Explaining Consciousness—the Hard Problem. Cambridge: The MIT Press, 1998.

(20) These observations can be accessed by the following method, outlined by Terence McKenna. Ingest 4—5 grams dried psilocybe mushrooms alone in silent darkness, in a setting that is safe and free from interruption. Note: This protocol is not an invitation to perform illegal acts. There are places on the planet where such an experiment can be carried out legally. For up-to-date information, go to Erowid.

(21) Fischer, Roland. “A Cartography of the Ecstatic and Meditative States.” Science, Vol. 174, Num. 4012, 26 November 1971.

(22) Tart, Charles T. “States of Consciousness and State-Specific Sciences.” Science, Vol. 176, 1203—1210, 1972.

(23) Lilly, John. The Deep Self. New York: Warner Books, 1977.

(24) Krippner, Stanley. “The Effects of Psychedelic Experience on Language Functioning,” in Aaronson and Osmond, eds., Psychedelics: the Uses and Implication of Hallucinogenic Drugs. New York: Doubleday & Company, 1970.

(25) R. Fischer, T. Kappeler, P. Wisecup, K. Thatcher, Dis. Nerv. Syst. 31,91 (1970).

(26) Munn, Henry. “The Mushrooms of Language,” in Hallucinogens and Shamanism, Michael J. Harner, ed. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1973.

(27) Munn, Henry. “Writing in the Imagination of an Oral Poet.”

(28) Noffke, Will (1989): A conversation over saucers. ReVision: A Journal of Consciousness and Transformation 11 (3, Winter, Angels, aliens, and archetypes: Part one), 23-30.

(29) McKenna, Terence. The Archaic Revival: Speculations on Psychedelic Mushrooms, the Amazon, Virtual Reality, UFOs, Evolution, Shamanism, the Rebirth of the Goddess, and the End of History. San Francisco: HarperSanFrancisco, 1992.

(30) Tart, Charles T. On Being Stoned: A Psychological Study of Marijuana Intoxication. Palo Alto: Science and Behavior Books, 1971.

(31) McKenna, Archaic Revival, 1992.

(32) Shanon, 2002.

(33) Powell, Simon. The Psilocybin Solution. Draft of an unpublished manuscript. (34) ibid, Powell.

(35) AD_05.03.27. (this is the filenaming convention I established for the research sessions. The AD stands for—playfully of course—Alien Downloads.)

(36) AD_05.04.01

(37) McKenna, Terence. True Hallucinations: Being an Account of the Author’s Extraordinary Adventures in the Devil’s Paradise. San Francisco: HarperSanFrancisco, 1993.

(38) An early description of the Glide project including animations of the Glide glyphs. (39) Powell, The Psilocybin Solution.